Thugs of Hindostan is a disaster, and it will remain so even if it makes some profit in the end, since more things than economics decide ‘success’ in cinema. It may be difficult to make this point to a Bollywood producer, but the success of a film venture is less dependent on the genius of the director and the technical or visual add-ons than on touching emotional chords with the film-going public, traceable to the socio-political issues of the day — though the political links may not always be visible. 3 Idiots (2009) had a message pertaining to self-actualisation just when the urban youth had been enthused by stories of Indians doing well in the global arena, and it celebrated the ‘Indian genius’. Patriotic films similarly latch on to sentiments in the public space but they need to tap the right kind of patriotism.

At the present moment, it would appear, anti-Pakistani sentiment is a more reliable way of bringing audiences into the halls than anti-colonial rhetoric, which is what Thugs of Hindostan offers. My own view is that anti-colonial rhetoric stopped being pertinent after the Congress era — since the Congress subsisted on the mythology around the freedom struggle, and kept the sentiment alive. Even under the Congress, the sentiment was already weakening and the last (moderately) successful anti-British film may have been 1942: A Love Story (1994), which was sold more on the basis of RD Burman’s music. If Lagaan (2000) was also ‘anti-British’, it tapped into cricketing patriotism, current to this day, rather than into any anti-colonial feelings. The anti-colonial rhetoric in Thugs of Hindostan is ludicrous and the film’s closest relative from Bollywood may be Manmohan Desai’s Mard (1985), a failed masala film; Thugs of Hindostan may also be described thus – as a failed masala film going through the motions of patriotism.

This leads us to the question of what a ‘masala film’ is and why Thugs of Hindostan cannot be termed a ‘successful masala film’. My view here is that a masala film is a difficult object to create and one of the few masala classics in Hindi cinema hitherto has been Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony (1977). A masala film by definition is a film that uses all the standard ingredients of popular cinema self-consciously, to the extent of making it border on its own parody. Amar Akbar Anthony, for instance, has all the ingredients familiar from films like Deewar and Yaadon ki Baraat – the sacrificing mother and siblings separated in childhood; there is also divine intervention when the villains try to get at the protagonists. The very shape of the miracle – a cobra which blocks their path into a sanctuary where a bhajan is being sung – is deliberately excessive, and a sophisticate cannot but laugh out aloud. At the same time, the film also allows some people to take all this seriously and it is not straightforward parody. The poor man played by Pran whose wife is afflicted by disease also invokes laughter (‘meri bibi to TB ho gaya hai’) although this again can be taken quite seriously as pathos by a segment. Another masala classic is David Dhavan’s Hero No. 1 (1997), which also borders on its own parody; part of its humour comes from Govinda’s comic imitation of Rajesh Khanna in Hrishikesh Mukerjee’s Bawarchi (1972).

It may seem that a masala film is generally without a message but it is almost mandatory for any popular film to have one; it would be more accurate to say that the masala film delivers an inflated message that can be read as self-mockery. It is not a half-hearted message but one that is almost nonsensical that makes for a masala film. Given this element, it may not be appropriate for a masala film to appear when political passions are running high. Amar Akbar Anthony came at the end of the Emergency when elections had already been announced and Hero No. 1 also when there was no strong political discourse in the public space. Just to give an idea of the political messages in masala films, in Amar Akbar Anthony, the children separated in childhood near a statue of Gandhiji can be read as Gandhian values not being able to unite the nation, and I take this to refer to the two Gandhians then opposing Mrs Gandhi — Morarji Desai and JP Narayan. Manmohan Desai was perhaps a Congress supporter since his later film Coolie (1983) also toys with Mrs Gandhi’s kind of populism. The original films that the two classics partly parody were serious efforts tapping into national sentiments and the timing of the masala films (and not only their inspired content) made them successful.

Thugs of Hindostan was initially announced as an adaptation of Confessions of a Thug by Phillip Meadows Taylor (1839), based on the Thuggee cult in India in existence for over 500 years. The Thugs were described as murderers and robbers and eliminated by the British when Lord Bentinck was Governor General. The man credited with destroying the cult was William Henry Sleeman and the town of Sleemanabad in Madhya Pradesh was named in his honour. With history being revised in the post-colonial era, the real truth about the Thugs was called into question, especially the notion of ‘criminal tribes’ created by the British, implying that everyone in a tribe could be branded a criminal. Thugs of Hindustan, which is now denying that it has anything to do with Meadows Taylor, appears to have hit upon the idea that Thugs were freedom fighters and embarked upon the project as an exercise in patriotism.

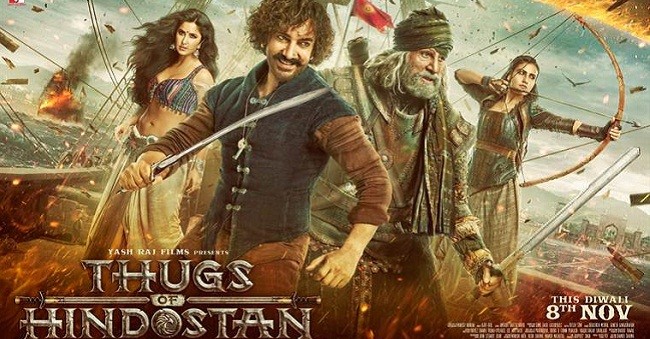

Thugs of Hindustan casts Amitabh Bachhan and Aamir Khan as principal characters and this casting itself reveals that it does not know which way it is going. Amitabh is evidently a tired man and even endorsing a ceiling fan may be making too many demands of energy upon him. He also takes the patriotism very seriously, as do the other bit players, something that the energetic Aamir Khan, wisely, does not do. Aamir Khan is probably the only one who had an idea of where the film might have gone. The film also brings in a British villain John Clive (perhaps brother of Robert Clive, the Company’s first Governor General) who plays his role very straight. I propose that a fake Britisher in a blonde wig reminiscent of Mogambo from Mr India (another successful masala film) would have served Thugs of Hindostan much better. Lloyd Owen who plays ‘John Clive’ is a genuine Britisher and a phony was what the film craved for – a fake Britisher as objective correlative to the fake anti-colonial sentiment spewed!

The film is being touted as the most expensive Indian film ever made but it is not a good strategy for a masala film to spend so much money. When the entire film is based on a fake premise visible from miles away, what is the good of trying to persuade the audience that it is all real? It is not always a good thing for a work of cinema to be sincere, especially when it is based on an unpalatable premise, but when it is insincere it should be conscious of its own insincerity, admitting to it without hesitation. Only such an approach makes for a great masala film, and Bollywood would do well to understand that.

Bollywood uses the word ‘fun’ rather loosely and film critics are quick to believe that the worst kind of trash can become ‘fun’ if only the spectator watched it with the right attitude (rather than a ‘critical’ one). My point here is that true ‘fun’ is difficult to produce; what happens most often is that people recognise that something is intended as fun and oblige the film-maker by mimicking ‘enjoyment’. This is like one’s polite response to a bad joke: one laughs simply in recognition of an intention rather than at genuine humour. Enjoyment is a component of happiness and we need desperately to convince ourselves that we are not unhappy. Since it takes discernment to recognise when one is not enjoying oneself, it is heartening that spectators and critics alike have given Thugs of Hindostan the thumbs down, implying recognition that true joy is not so easily to be had and only a successful work produces it. Perhaps Thugs of Hindostan will help audiences move to a new level of self-awareness with regard to the emotions that entertainment actually generates — rather than what publicity tells us it produces.

.jpeg)