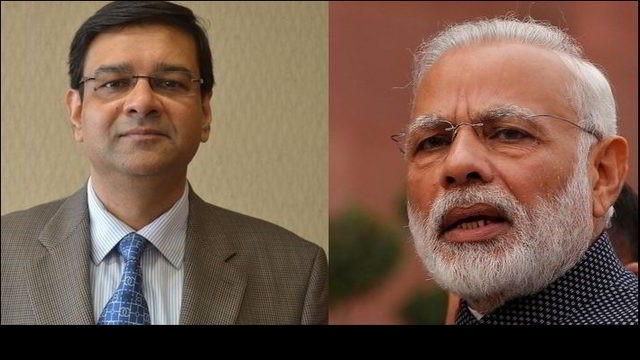

In the ongoing tussle between the Central government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), one thing has come out very clearly. Even when your own nominee is heading an institution, there is a limit to which you can push him, or her and not beyond. Dr Urjit Patel, Governor of the RBI, was preferred over Dr Raghuram Rajan by the government of India (GoI). And within two months after taking office, Patel approved the controversial demonetisation, the failure of which brought no laurels to anyone.

As frauds in banks started emerging, in increasing numbers, Patel started tightening the screws, an approach not to the liking of the government. And with the ‘reserves transfer’ issue cropping up, it appears to have become a villain in the eyes of the GoI, with the Finance Minister jeering at it and the Secretary, Finance Services, crossing swords with the Deputy Governor Acharya.

The news that the Central government is likely to crack the whip by using Section 7 of the RBI Act to and the consequent likely resignation of the Governor, was noted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which promptly announced that it would not countenance the attempts of governments of the member countries compromising the autonomy of their Central banks.

Why did things have come to such a pass? A popular government empowering the people’s mandate needs money to step up welfare schemes, particularly in an election year. And the RBI’s primary function is to ensure fiscal discipline and adherence to norms of financial prudence. But Patel, handpicked by the present government though he is, has his duty clearly cut out, and does not want to be seen as a puppet.

When Gurumurthi, a member of Swadeshi Jagran Manch – associate of the RSS - who was recently appointed to the RBI Board suggested that the RBI should transfer its reserves to the government, Patel bluntly refused. Now the head of the finance wing of the RSS has offered unsolicited advice to Patel that, in the event of his being unable to work with the government, he had better resign.

The major cause for all these troubles is the NPAs (Non-Performing Assets) and bad debts of banks. Over the decades, governments went on appointing their supporters as directors of the various commercial banks and furthered their interests by twisting the arms of the managements of those banks to lend to the persons and institutions of their choice.

As of today, NPAs are valued at Rs 10 lakh crores and the government-owned banks wrote off NPAs to the tune of Rs 3.16 lakh crore. The Punjab National Bank scam had clearly explored their weakness of their internal audit and oversight functions of the banks. The RBI belatedly woke up to the need for improved supervision and tight control. So, Patel refused to extend the terms of many CEOs of private banks and froze their severance packages.

In the case of the public sector banks, the Prompt Corrective Action (PCA) framework was made stringent. Earlier, PCA was rarely used to impose restrictions. But now RBI is keeping the deposits of 11 out of 21 commercial banks. The government wants more credit to be available in market to push up spending to create a feel-good factor. So, the nominee directors recently asked the RBI to release those deposits. The Governor did not cave in.

Simultaneously, the government wanted the RBI to lower interest rates, so that money would flow into market. When the RBI did not oblige and refused to discuss the interest policy with Finance department, Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramaniam openly criticised RBI’s interest policy. He also voiced his demand for a higher dividend (transfer of RBI reserves to exchequer) in order to ease the fiscal deficit caused by recapitalisation of banks. That proposal was not acceptable to the RBI which wanted to maintain the gold revaluation and contingency reserves at acceptable and safe levels.

The reserve is meant for meeting contingencies such as the decline of rupee value, depreciation in the value of the RBI’s holdings of the government bonds etc. But the Finance Ministry feeling that the technocrats in the RBI are too conservative and that, in any case, the money belongs to the government, wanted to use Section 7 of the RBI Act (which enables it to give directions to the Central bank). It is mandatory to ‘consult’ the Governor before doing so. Patel, who is not willing to toe the government’s line in this regard, appears to prefer offering to resign to obliging the government.

Stressing the importance of the issue in the present context, Deputy Governor Acharya warned, in a speech at a seminar, that if the RBI was not accorded the autonomy due to it, it would lead to the ultimate collapse of the financial sector and the day would soon come when the government would rue its approach. The Ministry of Finance attempted to contain the damage, stating that the autonomous status of the RBI would always be respected. But at the same time, Jaitley made derisive comments about the Central bank’s slack supervision in the past.

The Secretary, Financial Services, GoI, Subhash Chander Garg, also criticised Acharya personally. Speculation is rife that Patel is unhappy with the turn of events, and feels piqued as his reputation, which has already taken a beating on account of the government of India shifting to him the blame for the failure of the demonetisation scheme, will suffer much greater damage if he acquiesces in the proposal to transfer the reserves.

The GoI and the RBI seem to be having similar differences on various other important issues like writing off bad debts in power sector. This, in itself, is nothing unusual or unprecedented. It is the fact that the discord has come into the public domain that is unfortunate and regrettable. Undoubtedly the country‘s economy is in a bad shape.

The price of fuel is rising rapidly and the rupee is falling alarmingly as a result of which foreign institutional investors have withdrawn close to $5 billion from the Indian financial market in the last month. The collapse of the Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (ILFS) and its adverse effect on NBFCs (Non-Banking Financial Companies) is starving many sectors of access to the loans. This is a time when the government has to practice extreme restraint in expenditure. The RBI’s efforts to exercise fiscal control, need to be encouraged and certainly not discounted or, what is worse, ridiculed.

The Ministry of Finance and the RBI are, after all, different wings of the government, somewhat like the left hand and right hand of a person. It is only when they function in tandem that one can expect desirable results. In so far as the autonomy of institutions is concerned, it must be recognised that, while every government appoints only such people as heads of institutions whose ideology is compatible with its policies, it should, at the same time, realise that such persons cannot be pressurised beyond a point.

Governors of the RBI, without exception, have all been persons of great integrity, distinguished in their own fields and capable of holding and expressing independent views. And their job is not everything for them. Their reputation is high beyond our shores. It is unrealistic to expect them to flout accepted norms to please extant reserves. And, mainly on account of differences on policy matters, it is not proper to expose them to criticism by the functionaries of the ruling party.

And the present dispensation’s differences with Urjit Patel, who is their own choice, can only be put down to the government’s failure to appreciate in the imperatives playing the role of head of a prime institution. Unless this attitude changes, and changes very soon, one will not be surprised if the country heads for a substantial loss of credibility, a fall in its prestige internationally, and, ultimately, a serious financial crisis.

.jpeg)