“I was offered to write about what the release of The Accidental Prime Minister means, as election season approaches,” I tell her, and look away from her eyes, into a plate of lunch. For fear of identifying those foods publicly, let’s just call them spinach.

“And will you write under your name?” she pries open a roast potato.

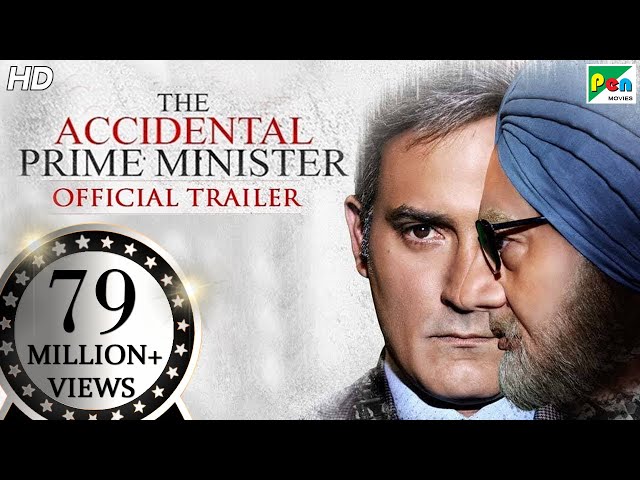

The trailer of The Accidental Prime Minister is a raging Twitter hashtag. The first look shows us a mostly-craven ex Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, of the Congress party. On a good day, he is bumbling his way through sensitive political issues of his time, like the nuclear deal with the US, and the Kashmir conflict. All the while, buckling under the piercing gaze of the then party president, Sonia Gandhi, who looks equal parts dynastic and plastic in these images. The upcoming film is instantly appropriated by the ruling Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP), whose official handle has tweeted the trailer claiming it's a "riveting tale of how a family held the country to ransom for 10 long years".

The Congress has dismissed the trailer as “fake propaganda”.

“Why wouldn’t I write under my name? I strongly believe that all films have the right to exist,” I’m baiting my old friend.

“As should your freedom to critique. Does it exist any longer?” She looks around, for fear of being heard. You can tell a political animal by how her eyes grow darker in this moment. Her personal life disallows her from expressing political opinions in public, so she talks openly only in private. And works an innocuous job, a shamelessly high-paying one, selling car tyres.

“We’ll find out. Today is a day good as any. I’ll need to keep my phone on, and take a call. Sorry about that, I’ll keep it short,” I promise.

“So there’s a storm coming, Mr. Wayne?” She whispers, playing Catwoman with a mask.

“You sound like you’re looking forward to it.” I Bruce Wayne her.

My film, Searching for Saraswati, co directed with Amit Madheshiya, is being reviewed by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) today.

The film is set in the backdrop of the ruling Bhartiya Janta Party government in Haryana declaring they have found ancient river Saraswati, which is believed to have been lost 5000 years ago, and was since found only in myth. While the film builds a critique of the project, it also seeks to explore the place of individual faith, through the belief systems of a farmer who has abandoned home in pursuit of the river, a Donald Trump-quoting godman and a Right to Information activist.

“They don’t believe it is real.” It is my film certification agent, calling after the screening at the Board’s Office in Mumbai.

“Yeh Censor mein atkegi,” he adds. This will not make it past the “Censor”.

Given that the Certification Board wantonly extends its ambit for certifying films into passing qualitative judgments on them, and consequently also censoring them, the agents have telescoped the name of this government body into “Censor”.

“The Censor wants to know how you can depict the search for Saraswati as a government project.”

“Well, unbelievable as the search for Saraswati might be, I have not made it up.”

“I don’t have time for emotions. What is your source?”

“The government. In the film, you can see the government officials talking. I suppose the government should believe themselves.” I say “government” three ways. And ask him to remind them, that I had also sent a letter a few days ago, detailing out the same explanation.

“I’ll see what they say, and call back,” he says, using the tone one reserves for “Try-telling-them-that.” He hangs up.

Smoke billows from the open kitchen of the restaurant.

“So how do you prove that a documentary is a documentary?,” she asks, in that remarkably gifted way of old friends, privileged to make your life harder.

I think of a very long answer, about the treacherous terrain of the chimera that is truth: the thing that documentaries are believed to represent, that there exists no unicorn called objectivity, and how we need to recognise the subjective nature of all kinds of filmmaking as being born of multiple decision making.

“Can someone say tomorrow, that The Accidental Prime Minister is a documentary?,” she chuckles. She’s enjoying this show.

Anupam Kher as Manmohan Singh in a still from The Accidental Prime Minister

Anupam Kher as Manmohan Singh in a still from The Accidental Prime Minister

“That would still not make it “true”. On the face of it, Leni Riefenstahl also made “documentaries”. It is disputed if the Nuremberg rally that we see in Triumph of the Will was staged for the cameras, but that is not quite the question for me. The meaning of that work, is,” I say.

I’m reminded of Hemingway’s credo to cut through moments of doubt. “Write the truest sentence that you know,” he urged. So I say the one more thing I know to be true: “In matters of craft, the film has to give us a way of looking at it.”

It is of note to consider that the makers and actors of The Accidental Prime Minister have variously claimed it as being based on “facts”. In this case, the eponymous book, a memoir of Sanjaya Baru — Manmohan Singh’s then media advisor. But facts, unto themselves, do not illuminate. It is their political deployment, which gives them meaning. And so, I believe, none of us remains a political innocent. Neither film makers, actors, nor audiences.

So when Anupam Kher, prominent BJP supporter who plays Manmohan Singh in the film, upon being asked what it might mean for the elections, insists, "Look, when the audience is going to the theatre to watch a film, they are regular cine-goers and movie lovers. They are not entering the hall as a voter," he is assuming a political vacuum for receiving films. One that does not exist.

The agent calls again.

“The Censor might agree to certify your film. But whatever this is, it is anti-government, they say.” He is also affronted that I did not warn him the film is about the government. “Is that automatically supposed to be a warning?,” I refrain from retaliating. For now, I am lost in the sheer joy of my work being allowed to exist because it is generously accepted as “whatever”.

Not so soon. “They will only certify it if you agree to cut a dialogue,” he adds, unfeelingly.

In the film, P. P. Kapoor, the Right to Information activist, is decoding the political motivations for the government’s furious search for river Saraswati. Here are his words, that have offended the Certification Board.

Unki jo philosophy hai, woh Hindu rashtravaad hai. Uske andar koi logon ko rozgaar dena, shiksha dena, mehengaayi door karna, mahilon ki suraksha…yeh koi sawaal nahin hain. Janta ko sirf yeh santushti miley, ki bhai yeh sarkaar tumhaare liye jo hai, tumhaare dharam ke liye, tumhaare rashtra ke liye, jo hai dekho, kitne bade bade kaam…paanch hazaar saal puraani nadi dhoondh ke le laaye, poore desh mein Sanskrit laagoo kar di, pathyakram mein Gita laagoo kar di, yogabhyaas ka International Yoga Day manaa diya…beef ban kar diya…yeh tamaam jo hai, sawaal jo hain, inke oopar logon ko golbaddh kiya ja raha hai.

(Hindu nationalism is their philosophy. It does not concern itself with employment, education, fighting inflation or the safety of women. So, they just want the public to believe that this government is working for your country and your religion. And so they go to find a 5000-year-old river, make Sanskrit compulsory in the country, introduce Gita in the syllabus, celebrate International Yoga Day, ban beef…this is how they are uniting the public.)

“So now they believe the film enough to ask us for a cut?,” I wonder.

“Yes, and they believe your film is anti-government,” he repeats the message.

“I am well within my rights to critique.”

“See, a lot of films are stuck at the Censor this year,” he tries empathy.

“Doesn’t make censorship right.”

“Madam,” he says, deliberating over all its syllables. Over two films of working together, my certification agent and I have developed a language where he gets to coalesce all his arguments under that one word: Madam.

“Why don’t people try making films that would be popular with the government? Those pass easily.” He extends me the courtesy of a few more words. End of the year generosity, I suppose.

Still from Thackeray trailer. YouTube screengrab

Still from Thackeray trailer. YouTube screengrab

I think of the recent crop of political films like Uri, Thackeray and the biopic PM Narendra Modi. As of now, we have trailers of the first two. The “outsiders” are the enemy; sometimes they lie outside our political borders. The trailer of Uri celebrates the purported surgical strikes by India on Pakistan in retaliation for its incursions in Kashmir. The “naya Hindustan” (new Hindustan) is advocating khoon ka badla khoon (blood for blood).

Thackeray is a film about Balasaheb Thackeray, founder of the right-wing outfit Shiv Sena in Mumbai, who celebrated that he had much in common with Hitler, and was indicted by the Srikrishna Commission for inciting violence in the Bombay riots in 1992.

These trailers glorify the confirmed patriots who go about executing muscular, militaristic ideas of India. If trailers are anything to go by, the films would bear scant openness, or zeal, to explore the complexities of these vexed ideas. In fact, they advocate a definitive rallying cry in the name of nationalism. Sure, these films must exist. But so should the space for dissent.

The agent wonders if has lost me.

“Hello! Are you there? It is the last day of the year, and post-lunch already. If you don’t accept the cut, the certificate will not be issued this year.”

I desperately seek a metaphor for our collective freedom of expression, and how broken it stands, over the last four and a half years. I would find it the next day. The news would tell me that the Palamu district police in Jharkhand, pre-empting a protest by para-teachers at Prime Minister Modi’s upcoming rally, has banned entry of anything that is black, inside the venue. The missive from the Superintendent of Police will read, “Government employee/common man will neither wear black pant, shirt, coat, sweater, muffler, tie, shoes, and socks nor carry black shawl, bag, cap and a piece of black cloth to the PM’s meeting venue.”

This one act of banning was later withdrawn, but there have been many and continued instances in the country where dissent has been steamrolled as “anti-national”. It is the structures of power that dictate who gets to express what. I cannot help but think again, of one of the most perverted deployments of cinema in history: to promote fascism, racism and genocide during the reign of Hitler. I think of his best-known film executive, the director Leni Riefenstahl. In his obituary of her, Richard Falcon wrote, “Her films are a challenge to historians and cinephiles alike, posing difficult questions about the relationship between 20th century’s greatest tragedy and its most powerful art form.”

Vicky Kaushal in Uri: The Surgical Strike

The meaning of this new crop of political films releasing before our elections cannot be cleaved from our current political environment. I do not have the luxury of invoking T.S. Eliot who declared: “I have assumed as axiomatic that a creation, a work of art, is autonomous.” Or Roland Barthes, who famously claimed that the author is dead. (And so, it is the reader who makes and remakes meaning.) The question of who creates meaning, cannot be divorced from the consideration of who has power to allow it.

“Without any sense of critique, we would merely dismiss The Third Reich and the cinema of Leni Riefenstahl. We’d even risk forgetting the seriousness of that cinema,” I trail off.

“For one, her work did define the language of much of the cinema that came after her,” my friend muses.

I think of the sinewy bodies of divers in action, rendered in slow motion in her film Olympia. We continue to make images like that.

“But, we also have to look at art as the result of personal political choices. Within, or without power structures. We can’t just say that the Third Reich hired her as a propagandist, and so this work came to be,” she reasons, bringing us to the altar of artistic choice.

“Yes, the idea of “pure cinema” is as irreconcilable as Leni insisting she was “apolitical”,” I admit. Artists do not work outside their beliefs and value systems.

In 1960, the National Film Theatre in Germany invited Leni to give a lecture. Its then controller Stanley Reed had declared that "Satan himself is welcome at the NFT if he makes good pictures."

Unfortunately, the invitation was later withdrawn.

The Accidental Prime Minister releases in three days.

.jpeg)