The Lok Sabha passed the controversial and contentious Citizenship Amendment Bill on Wednesday. The political Opposition and several civil society groups in the Northeast responded to the introduction of the bill in Parliament by observing a bandh in the region. Irrespective of its fate in the Upper House, the proposed legislation has polarised the Northeast and triggered a process of social and political realignment. Most disquietingly, it threatens to expose the faultlines that had led to the rise of subnationalist politics in the region in the 1980s.

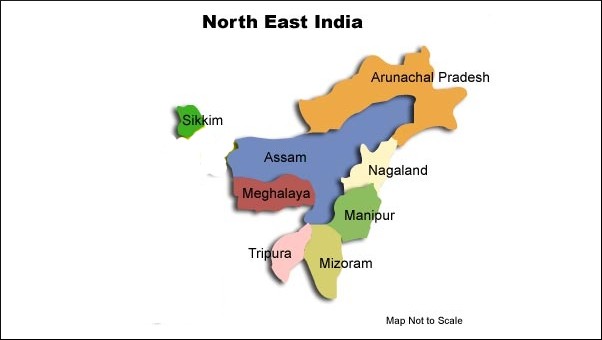

The BJP has been expanding its footprint in the Northeast ever since it won the 2014 general election. The party now runs governments in Assam, Manipur, Tripura and Arunachal Pradesh whereas its allies are in office in Meghalaya, Nagaland and Mizoram. However, its allies are distancing themselves from the BJP over the citizenship bill. On Wednesday, the Asom Gana Parishad, the political face of Assamese subnationalism, withdrew its ministers from the BJP-led government in Guwahati and quit the NDA. Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma has said his party, a constituent of the NDA, is opposed to the bill. The Indigenous People’s Front of Tripura (IPFT), again an ally of the BJP, supported the protests in Tripura against the bill. Mizoram Chief Minister Zoramthanga, another NDA partner, has also opposed the proposed law. The political churn reflects the fact that questions concerning ethnic and linguistic identities have underpinned politics in the region for decades. However, the subnationalist narrative in the region so far focussed on opposition to the “foreigner”, and has been indifferent to religion.

The Citizenship Amendment Bill, which privileges the claims of non-Muslim migrants, has sought to twist this narrative. BJP leader Himanta Biswa Sarma has painted the spectre of Muslim separatism to build support for the bill. This is a divisive and dangerous idea, especially in Assam, where Muslims constitute over 34 per cent of the population and many Muslim outfits support secular opposition to illegal migration. The citizenship bill also complicates the NRC process since it advances the cut-off date for non-Muslims seeking Indian citizenship to 2014 from 1971, the year agreed upon in the Assam Accord. This would mean that a significant percentage of the 40 lakh people who may turn stateless once the NRC is updated will qualify for Indian citizenship, a prospect that alarms subnationalist forces in the Northeast. The BJP has sought to assuage such fears by promising extra protection to indigenous communities. The emphasis on exclusivist identities is a fraught proposition. The BJP is exposing a new faultline by proposing that religious identity be the marker of citizenship.

.jpeg)